It was so easy to go bankrupt if clients took years to pay their bills, so enticing to dodge duty and fudge the marks on a recently-made piece, so tempting to risk transportation by stealing a teaspoon if you were hungry. And, once an antiquarian interest developed in old silver, it was a simple matter to work late and make a few fakes to sell to the unwary.

The bad news for the culprits is that hallmarking regulations are upheld by statute, and the melt value of the raw material made burglary and pickpocketing a high-risk strategy. The good news for present-day researchers is that those who were caught are recorded in court proceedings, newspapers and the archives of livery companies. Many of the finest eighteenth-century silversmiths went bankrupt: some continued working and prospered again, others never quite recovered.

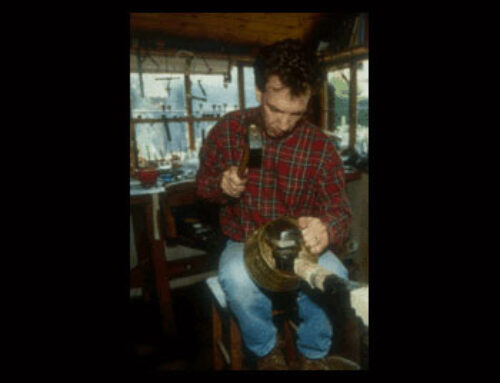

And why is the bowl chosen to illustrate this page? When examining any piece of silver you should always cross-question yourself about it and hope that, like this piece, you can prove it innocent of any malpractice. This is a good, honest object, of typically Scottish form.

View list of relevant Silver Studies articles